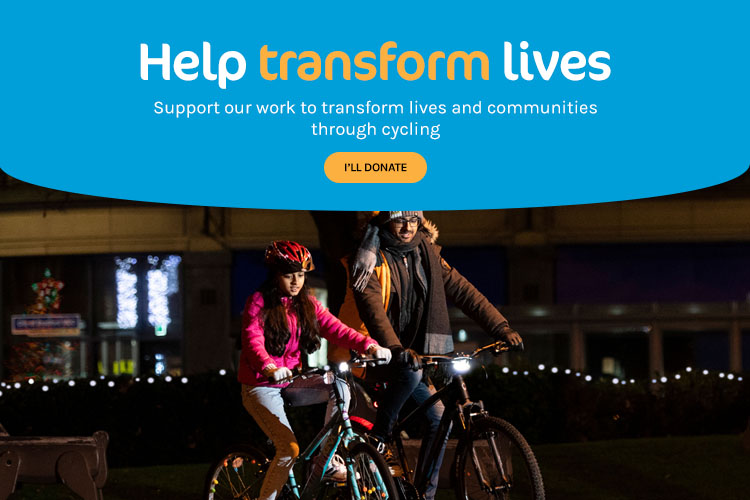

Our mission is to enable millions more to cycle. As independent experts we are able to offer a range of impartial advice, guides, reviews, inspiration and routes to help you experience the joy of cycling. We also have community projects and a network of thousands of clubs, groups and events

All about bikepacking

Multi-day off-road adventures by mountain bike – the best bikepacking tips and advice