Why should the Government update, improve and rationalise cycle design guidance?

Why should the Government update, improve and rationalise cycle design guidance?

Important update!

We are pleased to report that, in July 2020, the Department for Transport published the new guidance on cycle infrastructure design (LTN1/20) we were waiting for. We will be revising all our advice, policy and materials on infrastructure in the light of it as soon as possible.

Please also note existing cycle infrastructure design guidance for London, Wales and Scotland (revision due). Plus, technical guidance for Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plans (LCWIPs, England).

Original article:

Firstly, Cycling UK is pleased that the Government is already taking steps to update Local Transport Note 2/08 Cycling Infrastructure Design (LTN 2/08), the main guidance available from the Department for Transport (DfT).

This is necessary because local authorities are currently working not just from LTN 2/08 in some cases, but from myriad sources, including: locally produced advice; Manual for Streets/Manual for Streets 2; or the Interim Advice Note (IAN) 195/16, Cycle traffic and the Strategic Road Network.

This results in:

- The plethora of design standards, some of which are not clearly drafted;

- An inconsistent approach to cycle design from one highway authority to the next;

- Confusion to cyclists and other road users alike; and

- Too much provision that is low-quality and, in many cases, downright dangerous.

The need for a single document and a modular approach

We urge the Government to combine all relevant guidance notes into one ‘Street Design Manual’, and adopt a modular approach in the fashion of the Traffic Signs Manual, i.e. with separate sections released as resources permit.

Such a document should include various specific chapters setting out standard designs, street cross-sections and recommended approaches, following the example of the Design Guidance for the Active Travel (Wales) Act, and IAN 195/16.

The guidance should also encourage local authorities to use many of the changes brought about in Transport Signs Regulations and General Directions (TSRGD) 2016 and previous guidance, including: low-level signals; parallel zebra crossings; and the use of ‘elephant’s footprints’ to mark cycle crossings (such markings should also be given the status of priority crossings).

What the guidance should say and do

Allow for innovation:

The updated guidance should allow for innovation, but set safety-critical minimum standards alongside ‘normal’ standards that require written justification if not met. Subsequent revisions should incorporate suitably evaluated and successful innovation.

Cover the needs of other road users, planning for disability and the Public Sector Equality Duty:

Whilst current conditions in the UK deter many people from cycling, research shows they disproportionately affect children, older people, women and people with disabilities. These are all groups with ‘protected characteristics’ under the Equality Act 2010.

Hence, in carrying out the revision of LTN 2/08, The Department for Transport (DfT) is obliged under the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) created by that Act, to seek to overcome the obstacles in the way of increased cycle use among these groups.

In addition, the guidance should direct local authorities on the importance of planning for other road users’ needs when designing for cycling. This is because, in some cases, the preferred design for cycle users conflicts with the needs of, for example, pedestrians, wheelchair users, blind and visually impaired pedestrians, buses and their passengers, plus motorcyclists, freight, and private motorists.

It should be noted here, however, that some people use their cycles as a mobility aid. They too can encounter problems, especially if they ride adapted, non-standard machines: for example, barriers to prevent the illegal use of motorcycles on greenway routes are often difficult and sometimes impossible to get past. Guidance must therefore unequivocally state that the installation of such barriers is not recommended, unless circumstances are exceptional.

Explain which type of infrastructure is advisable, and where:

Cycling UK believes that infrastructure for cycling falls into three basic criteria:

- Physically protected space for cycling along busier roads;

- Streets designed to filter out motor traffic as much as possible, with low speed limits;

- Routes entirely away from motor traffic, integrated with the wider cycling network.

These are covered in detail in our article on the main principles of cycle-friendly design.

The problem of low-quality cycling infrastructure

Before analysing how and why low-quality cycling infrastructure is built, it is worth noting the problems it causes.

Reallocating road-space for a cycle lane or track that proves impractical or unsafe to use is, for instance, likely to be highly damaging: not only is it a direct waste of resources and jeopardises future investment, but it also risks compounding oppositional attitudes between road users.

This conflict lies in two opposing ‘logics’ of drivers and cyclists, identified by Christmas et al, (2010).

The ‘driver logic’ is simplified thus:

- Bikes are anomalous and really do not belong on the road;

- They should be given somewhere else to go;

- Having been given somewhere else, they should not then be on the road;

- Nothing should be taken away from drivers in the process.

In direct conflict with this lies a ‘cyclist logic’, which argues that cyclists should not be forced to use cycle facilities. These two opposed views will continue to co-exist and be mutually reinforced by the provision of poor infrastructure. At its worst, this can lead to open hostility between road users, as documented in countless incidents captured on bike or helmet-mounted cameras.

Why does bad design persist?

Quality of design is hampered by various factors. These include:

- the absence of political leadership to endorse challenging schemes;

- inadequate funding to achieve the preferred solution;

- lack of good design skills or execution; and

- perverse results from road safety audits.

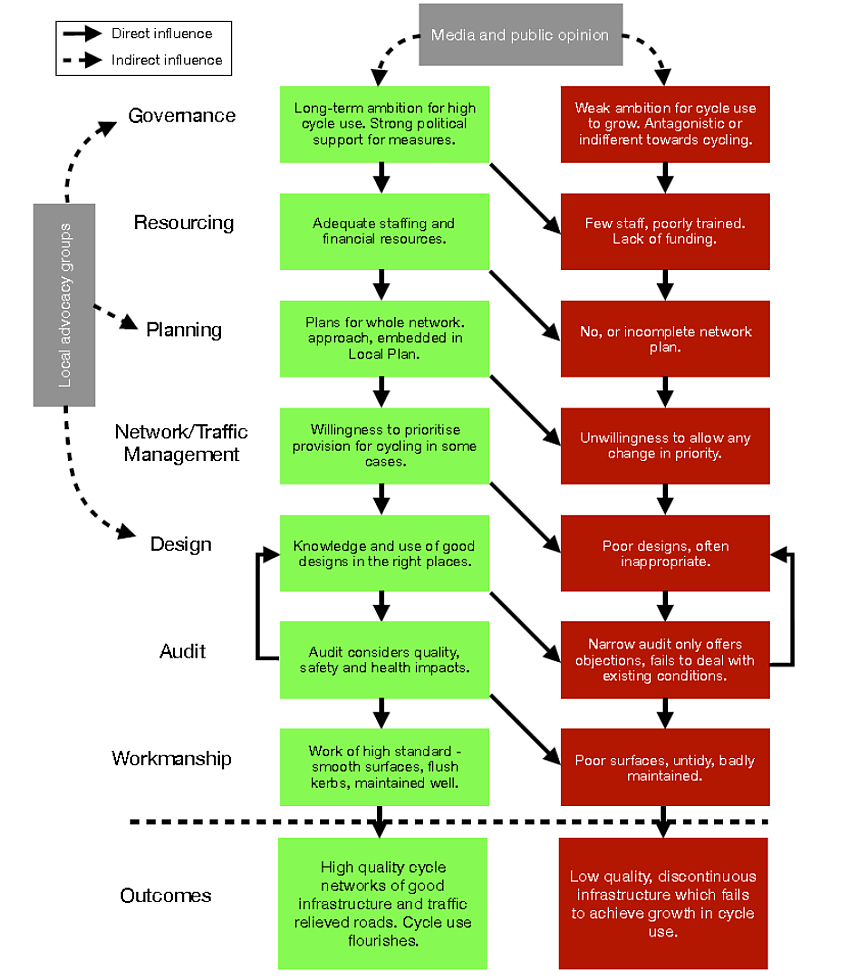

‘Bad’ design, is not inevitable, however. The stages of production of infrastructure, and how this can go from good to bad, is set out in the diagram below. At each stage, a weakness in the chain can mean that poor quality infrastructure will still result.

A simplified model of the production of good or poor-quality cycling infrastructure

The flowcharts above show the steps required for good cycle networks to develop.

At each stage, the production of good quality infrastructure can be undermined: even with strong political ambition, a lack of resources - either of well-trained staff or funding - could still lead to poor network planning, or compromised designs; even with a willingness to prioritise cycling, poor design can undermine it; without agreement to reallocate road-space or alter junction capacity, routes will inevitably be lower in quality, even if the network plan is comprehensive and well thought-out, etc.

In other words, once an element of the chain is missing, it is harder to achieve a good outcome. This means that ensuring any national standards are consistently applied will also require:

- political will and commitment at the local level;

- consistent and reliable funding;

- well-trained staff;

- good stakeholder engagement; and

- good audit and quality control processes.

Road Safety Audit vs public health

While better guidance is vital, it will not be sufficient on its own to overcome the persistent problems of poor and often dangerous cycling conditions in England. Much of this, Cycling UK believes, is due to the asymmetric approach transport policy takes towards public health and road safety for pedestrians and cyclists. In some cases, this continues to deliver perverse results.

Although Road Safety Audit (RSA) can provide a useful check on the street design process, and urges careful consideration of pedestrians and cyclists, the results can sometimes inhibit designs that will provide better for them.

In other words, the upshot may neither encourage active travel, nor reduce motorised traffic volumes. Indeed, RSAs can all too often frustrate rather than support these aims.

For instance, staggered pedestrian crossings with guard-railing may corral some users, but if the railing ignores the desire line, others will simply ignore the formal crossing entirely, choosing to dash for a gap in traffic. Similarly, the proliferation of ‘Cyclists dismount’ or ‘End of route’ signs, often installed as a means of fulfilling an RSA, will lead to bafflement, frustration and a reluctance to use the route by many cyclists.

Wide application of the new guidance

Given the need to ensure maximum value for cycling from the limited funding available, it is also vital that the new guidance is consistently applied in designing and planning all highway traffic schemes (i.e. not just in those described as cycling and walking schemes), and indeed in new developments and planned highway maintenance works.